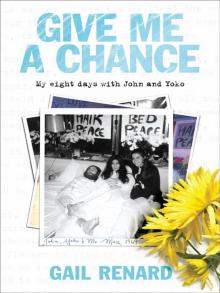

- Home

- Gail Renard

Give Me a Chance Page 2

Give Me a Chance Read online

Page 2

John explained, “It makes a change. Most people who approach us want something!”

I could see that John just wanted to be treated like everyone else, which I could understand. It must be boring when people scream every time they see you, or don’t treat you like a real person. I vowed to myself that I wouldn’t do either. I gave him the Hershey bar, relieved that there wasn’t any fluff stuck to it.

Here’s the Hershey-bar wrapper from the bar I gave to John. Ten cents bought a lot of chocolate in those days.

As he munched away happily, I told the Lennons that the only famous person I’d interviewed before was Patrick Macnee, who played John Steed in The Avengers on TV, and that had been by letter. So I warned them I might not be any good at it.

An extract from my original diary (including the mistakes!), which I typed up every night.

John was immediately interested about Patrick Macnee and wanted to know all about him. He was delighted to hear that the actor was down to earth – “I always thought he was posh and upper-class, like you see on the telly.”

I kept wanting to pinch myself, because here I was gossiping about my favourite TV show with John Lennon, just as if he was one of my mates. It was surreal. He didn’t eat all the chocolate (more restrained than I’d ever be) but handed some of it back, which I put carefully in my pocket. I knew I would keep it for ever … not the chocolate, obviously, but the wrapper, which was going straight into my diary, because John had touched it. Then I remembered why I was here and I didn’t want to waste my golden chance to get this scoop. I wanted to look professional, so I took out the pen and notebook that I always carried in my bag. Putting on my best reporter look, I asked John and Yoko why they were in Montreal.

The Lennons explained that they hoped to have a Bed-In, to campaign for peace. There were many wars raging at the time, including in Vietnam and Biafra. That was all we saw when we switched on the telly or read the newspapers. War made the world look a scary place, especially when you saw teenagers being sent into battle.

John and Yoko wanted to stop all wars. They wanted to speak to countries about settling their problems in a peaceful way, instead of automatically turning to fighting as a first resort. I was against war too, and was always excited to find people who felt the same way as me. It wasn’t often that I agreed with adults, but I was with the Lennons heart and soul on this.

There were problems where I lived too. Montreal had both English- and French-speaking people, and they argued over which language should be used. Actually it was more than just arguing. The whole thing got extremely violent at times and there were bombings across the province. I found this terrifying. I couldn’t understand why everyone couldn’t just speak both languages, as I did, and get along together. I was eager to do anything I could to further the Lennons’ cause.

Their plan was to stay in bed for eight whole days to get the attention of the world’s press; John knew that anything he did caught the public’s imagination straight away. They had originally wanted to hold their Bed-In in America, but John hadn’t been able to get a visa, so they weren’t allowed in. Next they’d thought about going to the Bahamas, but John couldn’t imagine staying in bed for a week in all that heat and humidity. The Bahamas’ loss was our gain.

Luckily for me Montreal is only forty-five miles from the American border, so the Lennons chose to come here instead. John decided, “If I can’t go to the world, maybe, if they know where I am, the world will come to me.”

And right now it was I who had come to John and Yoko, and was sitting there with my pen and paper. I was determined to do my best to write everything down properly, because I felt I must do the Lennons’ peace message justice.

Just as we were about to begin, a trendily dressed man came into the room; I recognized him from all the fan magazines. John introduced me to Derek Taylor, the Beatles’ press officer, who took care of the band whenever they were interviewed by the newspapers, TV or radio – a job that certainly kept him busy. He decided who should speak to the Beatles and when.

Derek was wearing a bright red jumper with fashionable Carnaby Street flared trousers, and had a smile as big as his impressive moustache. I was a bit worried he might throw me out, but he was very welcoming.

Derek Taylor, the Beatles’ press agent, a dedicated follower of fashion and a fabulous man.

Derek and the Beatles had known each other for years, ever since they’d all started out in Liverpool around the same time. The Beatles had been unknown then, as was Derek, but he saw one of the band’s early concerts and was bowled over by their music. He was one of the first journalists to give them a rave review, after which they all became mates. As they became more famous, the Beatles gave Derek a job as soon as they could.

Although they’d only just arrived, Derek was already beavering away, setting up meetings. He told John and Yoko about a local DJ who wanted to interview them. I was surprised when, for some reason, John seemed to react very strongly against that particular man: “No, I don’t want to do a show with him. I’d rather be interviewed by anyone else!”

Derek listened patiently, then asked, “So who do you want to do the show with?”

John thought for a moment, then looked my way, pointed at me and said, “I’d rather be interviewed by Gail!”

I was flabbergasted. What had he just said? I couldn’t have heard right.

John was looking at me intensely. “Would you like to interview us on the radio?” he asked.

That’s rather like asking if you’d like to win the lottery and have a year off school, with free ice-cream thrown in. Was he serious?

As if that wasn’t enough, John had a word with Derek, then added, “The interview won’t be until this evening, so would you mind hanging out with us for a couple of hours?”

OK, now I knew this was a dream. This sort of thing just didn’t happen in the real world – and especially not to me. I’d gone for sixteen years without ever being asked to do anything like interview a Beatle. Right now I should be at home, not doing my homework or not tidying my room. That was life as I knew it. But John, Yoko and Derek were all looking at me, waiting for an answer.

I’d never done a radio show before. Then again, I’d never met the Lennons before. I guessed there was a first time for everything and it seemed to be today. But even though I was in shock, I’d been well brought up, and I knew my mum would go spare if I missed dinner without telling her. “Could I ring home, please?”

Derek laughed and handed me the phone.

I was surprised I could even remember my own number. When my mother answered, I tried to sound calm but ended up shrieking, “Is it all right if I’m home a bit late? I’m at the Queen Elizabeth Hotel, and I’m going to be on the radio with John and Yoko!”

My mother was used to me joking; this time I had to convince her I was serious. I really was at the hotel with the Lennons, and we were going to be on air together. When she realized I wasn’t kidding, she was as pleased as I was – she knew how much I loved the Beatles. Of course she did; she’d heard me talk about nothing else for the last six years.

Mum wished me good luck, and I asked her to ring my million closest friends to tell them to listen to the radio too. I’d have given anything to see their faces, though just imagining them was pretty good too.

I hung up, wondering what would happen next. I’d never hung out with a rock star before, not even for a few minutes, let alone a few hours, so I didn’t have a clue. In the teen magazines, celebrity life looked all glamour, clubbing and excitement. But I quickly found out it wasn’t quite like that.

While Yoko went to put little Kyoko to bed, John switched on the telly. That was fine, although it didn’t seem very show-biz to me – especially when the TV didn’t work properly. John was disappointed because the colours were all fuzzy and it was impossible to get a clear picture.

Derek called the front desk, but I knew what was wrong.

“Oh, we’re always having the same problem with o

urs,” I said. “Would you like me to fix it?”

John thought we had nothing to lose, so I did what I always did at home: I smacked the TV on the side with my hand – and suddenly the picture was perfect. John laughed, “You should have been along on the Beatles’ tours. The colour on the tellies was always lousy then!” He made himself comfy on the settee, wondering aloud what was on.

I remembered that one of my favourite films, the Beatles’ very own A Hard Day’s Night, was showing that evening. They’d made it five years before, but I still couldn’t get enough of it. I joked that it was a pity that I wasn’t home, or else I’d be watching it and I could see John on TV.

It dawned on him that he hadn’t seen the film for years, and motioned for me to sit down beside him. “Then let’s watch it here. I’d like to see it again.”

I thought I’d died and gone to heaven to be sitting with John, watching A Hard Day’s Night. The last time I’d seen it, I’d queued for hours in the pouring rain outside the Capital Cinema in St Catherine Street to get a seat. And then I had to sit next to a girl who yelled so loud I couldn’t hear myself scream. This time was more comfortable, even though there wasn’t any popcorn. Still, you can’t have everything.

The title music started and as the Beatles sang, my heart raced. We watched the film’s first scene, in which John, Paul, George and Ringo are being chased down a street in London by hysterical fans. I shared their excitement. I looked at John sitting next to me, then at John on the telly, then back again. I’d never known anything so strange in my life. As we concentrated on the film, it struck me that although it had been made in black and white, in some magical way my life had just turned to Technicolor.

Soon afterwards, a technician from the radio station arrived to set up the equipment for the broadcast. We stopped watching the film – but that was all right, because John and I both knew how it ended. Then it hit me that I was going to be on live radio with the Lennons and I wasn’t prepared. I felt a bit sick. It was like going into an exam I hadn’t studied for (and I knew that feeling well). I thought quickly of some questions; that wasn’t too hard – there were so many things I was dying to ask, I could have been there for ever. I wrote them all down in case I got stage fright and froze on air. Whatever happened, I didn’t want to let John and Yoko down after they’d shown so much faith in me.

Finally it was time for the show. John encouraged me just to be myself.

I started with something I wanted to know: “Do you ever go back to Liverpool, where you came from?”

He laughed. “I could never return to Liverpool with this long hair. I’d be mugged!” He added that he didn’t have to go there to see his beloved Aunt Mimi any more, because after becoming successful he’d bought her a bungalow in Dorset. John had lived with his aunt and his Uncle George after his parents split up when he was young, and I could see he loved her.

He also told me that the Beatles had been given awards, MBEs, by the Queen. MBE stands for Member of the British Empire, and the Beatles’ were awarded for their music and for being one of Britain’s biggest exports. John gave his medal to his aunt, which was a kind thing to do. He grinned that she kept it proudly on top of her telly, for everyone to see. (Little did we know that later in 1969, John was to return his award to the Queen, in protest against Britain’s involvement in the ongoing wars in Africa and Vietnam.)

Now we were rolling. I was beginning to relax, so I turned the interview to more serious subjects. After all, I knew John and Yoko were here to talk about peace. I was burning to hear what they had to say and hoped I’d be able to apply it to what was happening in Montreal. I asked what they hoped to achieve with their Bed-In.

John replied that they were doing it because “Most people want peace, not war.”

The Lennons explained that they wanted people who were against war to stand up and make themselves heard all over the world. Ordinary people’s voices were as important as the politicians’; even more so, if they all wanted the same thing.

“People have the power,” added Yoko. “All we have to do is remind them they have the power.”

John went on, “We’re talking to anybody who’s interested in peace, which is most people. Peace is all our responsibility, every one of us, and we can’t just blame the government or the Americans or anyone else for what they did. It’s all up to us.”

I’d never thought of it like that before, but what John was saying made sense. He wanted us all to realize that we had the ability to stop wars as well as start them, which was inspiring.

“Everyone has to be proactive. You can do it. You can change the world … I’m full of hope.”

I understood all that – but I wondered why he and Yoko had decided to stay in bed for eight days. How did they think that would help?

John made it clear that it was to get the attention of the world’s press, nothing else. They certainly weren’t doing it for themselves: “I don’t need publicity.” He preferred to spend his time making music, or being alone with Yoko, but this was something he felt was more important. The Lennons were doing all this purely to talk about peace.

Yoko declared, “We want to use our celebrity for good.”

John agreed that was all anyone could do. “Just be yourself, be accessible.”

I saw that the radio engineer was making turning motions to us with his hand. I wasn’t sure what he was doing but then I realized he was signalling to us to wind up the interview, because we were running out of time. It had all whizzed by so quickly.

I got in one last question. “What do you feel at the end of the day, when the rest of the world goes home?”

“Just tiredness and loneliness, my dear,” John sighed.

And that was that. Our interview was over just as I was getting warmed up; I’d have been happy to talk for ever.

After we came off air, John and Yoko told me their goal was to reach as many TV and radio stations as possible. I offered to look up the addresses and phone numbers of some American and Canadian stations for them, to get them started. They both liked that idea.

Yoko smiled at me. “You’re a creative woman.”

I was taken aback. I wasn’t used to being praised – quite the contrary. Sometimes when you have an older brother you get used to being called many things, none of them good. I’d certainly never been called creative before – or a woman, either. Just about everyone, at home, at school and throughout the universe, treated me like a kid, and a fairly useless one at that. But Yoko spoke to me as if I were an adult, and I liked it. She made me feel as if I could make a contribution.

Even so, I was stunned when John said, “It’d be great if you could come back tomorrow with a list.”

Did I hear right? People never asked me to come back a second time. Once was usually enough, and people often seemed to regret even that.

“You could help with the press and look after Kyoko,” John went on.

In my stunned state, it took a moment for the penny to drop. “You mean I can come again?”

John and Yoko smiled and nodded yes.

There was nothing I wanted more; it was as if I’d won the biggest prize ever. Still, I knew I would have to ask for permission or risk being grounded for the rest of my life. You know mothers.

Mum was always asking awkward questions. Every time I went out, I felt I should fill in a form, explaining where I was going, what time I’d be back, and why I couldn’t re-tile the roof or re-invent the wheel or do something sensible with my time instead.

I knew that today wouldn’t be any different, so I crossed my fingers and rang home again. When I told Mum about the Lennons’ invitation, she was as blown away as I was. But, as ever, she needed to know more. Something told me this questionnaire would be a long one.

My mum’s a little lady, barely five feet tall in her stockinged feet, but she’s also a protective Jewish mother and, trust me, you don’t mess with those. She’s descended down a long line of five thousand years of unstoppable Jewish moth

ers. The Lennons might be two of the most famous people in history, but she had never met them and I was still her little girl. If I was going to be spending much time with them, she’d need to know a whole lot more.

“Put John on the phone,” she demanded.

I recognized her inquisitor’s voice and was mortified. “Oh Mum, you can’t!”

She answered calmly, “Oh yes I can!”

I knew she could and she would, and that I didn’t have a choice. She’d never spoken to a superstar before, so I had no idea what she’d say. But I also knew my mum could handle herself in any situation and on her own terms. She made it clear that unless she was sure that I was safe and being well taken care of, I wasn’t going to be allowed to go anywhere. The ball was in my court.

Me in the topsy-turvy world of John and Yoko.

Years of experience told me to surrender sooner rather than later, so I reluctantly handed the phone over to John. I tried not to cringe as Mum carefully spelt out her conditions to him. There was to be no funny business – no sex or drugs around her innocent daughter. As if that wasn’t enough, Mum also said that I could help at the Bed-In during the day but I’d have to be back at home by my bedtime every night.

To my amazement, John agreed. (Not a lot of people disagreed with my mum and lived.) It dawned on me that Mum might have reminded John of his Aunt Mimi. Both were strong ladies to whom you gave the utmost respect.

By now it was getting late, and the Lennons were tired after their long day. It was time for me to go home. They didn’t want me going home by bus, so Derek rang to get me a taxi. As I was leaving, I suddenly panicked. What if, with all the tight security, I couldn’t get into the hotel again the next day? I explained my worries to John and said that I knew it was childish but, just in case I didn’t see him again, could I please have his autograph? I had to prove to myself that I hadn’t been dreaming.

Give Me a Chance

Give Me a Chance